An AI-illustrated flash fiction story (YouTube). Click the graphic below.

A couple of years ago I dove deeply into Korean Sijo. You’ll find a number of these poems on this website, some which have won prizes in international competition. First appearing in 14th century Korea, Sijo is longer than Haiku and goes beyond imagery into story telling. I think you’ll like playing around with this one. Read an article I that wrote to get you started HERE. It’s in PDF format so you can download and print it if you have a mind to. Let me know what you think.

A 10 minute video about the Korean short form.

The Way of the River: Sijo Poetry in English is my latest chapbook. It features many of my own Sijo poems and resource information on the Sijo form, including classical and contemporary examples. You can download a free PDF (Click the cover image).

The Way of the River: Sijo Poetry in English is my latest chapbook. It features many of my own Sijo poems and resource information on the Sijo form, including classical and contemporary examples. You can download a free PDF (Click the cover image).

Sijo is a concise Korean poetic form consisting of three lines, each containing 14-16 syllables, totaling 44-46 syllables. These lines feature a midpoint pause, akin to a caesura, although it need not adhere to a specific meter. The first half of each line encompasses six to nine syllables, while the second half should contain no fewer than five. Originally intended to be sung, Sijo typically explore themes of romance, metaphysics, or spirituality. Regardless of the topic, ideally, the first line introduces an idea or narrative, the second elaborates the theme, and the third offers closure, often with a twist. In modern times, Sijo are often presented in six lines.

The Case for Publishing Your Own Poetry and Giving it Away

Like many people, I came to writing poetry later in life, starting in my late fifties. After a few years of posting to a micro blogging site anonymously, I was ready to seek “legitimacy” through journal publication, so I began submitting and before long, I had some success. A few more years and I felt I had enough published poems that I should start thinking about a book. I put a manuscript together, did some research and chose a publisher that seemed likely to accept it. I was right. A couple of weeks after submitting it my manuscript was accepted by a small press that specializes in publishing poetry by lesser known and new poets.

The quality control my publisher used was a requirement that about a third of the poems in the manuscript had to have a prior publication credit. I exceeded that, choosing only poems with a publication history to include in my book. My goal was to have a published book of poems that an editor somewhere had already selected and published.

I knew going in that small publishers, including mine, didn’t have the resources to do much marketing. I was perfectly accepting of that limitation. I would buy author copies, schedule readings with local book stores and poetry groups where I could, and attend open mic opportunities. I also set up an author web page and social media accounts so I could do my own marketing without spending a lot of money.

My book was published in March of 2020, just as the country and the world went into Covid lock-down so my own marketing plans were blown up. My publisher made the publication announcement to their mailing lists and on their social media platforms. I published sample poems on my author website and social media, but that was the end of it. No readings, no open mics – just a couple of reviews on Amazon and on my local library’s blog.

A couple of years later, I was thinking about another book, so I took a deeper look into my previous experience beginning with some research about various models that publishers use. I discovered some troubling truths about poetry publishing.

One thing I learned is that poets at my level do not make money from having their books published. Only the publisher makes money. That’s how publishing poetry works. In my case, I knew that my publisher would make more than I did whenever a copy of my book sold from their web site or from Amazon – much more.

I learned that small publishers that want to profit have to publish a lot of titles because even their best-selling poets sell a few hundred copies at most and that most poetry books sell fewer than fifty copies. Those who do sell hundreds did so because they, and not the publisher sold them. That’s right, your publisher is not working for you – you are working for your publisher. You buy your author copies at a substantial markup, you sell them from your own website or at readings, book fairs or whatever and no royalties come to you from selling those author copies because your publisher has already made their profit from selling to you.

As poets, the numbers are not in our favor. To begin with, my published book is too expensive. How can I expect to sell a book of poems that costs more than a book by a well-known poet? Paperback books by Billy Collins, Ted Kooser, Naomi Shihab Nye or Ocean Vuong sell for between seven and sixteen dollars, depending on how old they are. The publisher set the price of my book at $18.50. I had no say in that. The author price for the copies I bought (I did get 5 free copies) was ten dollars each, a substantial discount, but that’s the price for me to buy copies of my own work and at that price, the publisher is making more from me than from all other sales.

I did some thinking about what I really wanted out of publishing my poetry and the conclusion I reached is that I wanted to share it with other people who appreciate poetry. I concluded the best way to do that is not through the traditional means open to me. I took a close look into self-publishing. I crunched some numbers. I found that I can get printed copies of a book of between 24 and 100 pages for $2.60 each (about $2.80 with shipping). At that price I can take books to a reading and sell them for three bucks or, better yet, I can give them away for free. But why stop there? Why not use my author website to give away free digital copies? If the sole purpose of publishing is to share my work as widely as possible, what could be better than making it free?

That’s exactly what I did with my next book, a chapbook that I published myself, I ordered thirty copies and sent them to my poetry friends. I was asked to do a presentation on self-publishing at a meeting of a state poetry society. I ordered fifty more copies and gave them away at that meeting. In the first six months the free version was downloaded 107 times from my web site and. on Amazon, ten print copies were sold for a minimal price.

This article was about the “why” of self-publishing. The “how” of self-publishing is something you can research on your own just as I did. I will tell you, there is a learning curve, but not one that’s insurmountable for most people. Learning is no more difficult than a 100-level college course.

Article Update: As of November 2024 free copies of my books have accumulated over 700 downloads. That’s about 200 books per year.

Watch a short promotional video of Haiga produced from Year of Moons: Haiku, Senryu and Sijo.

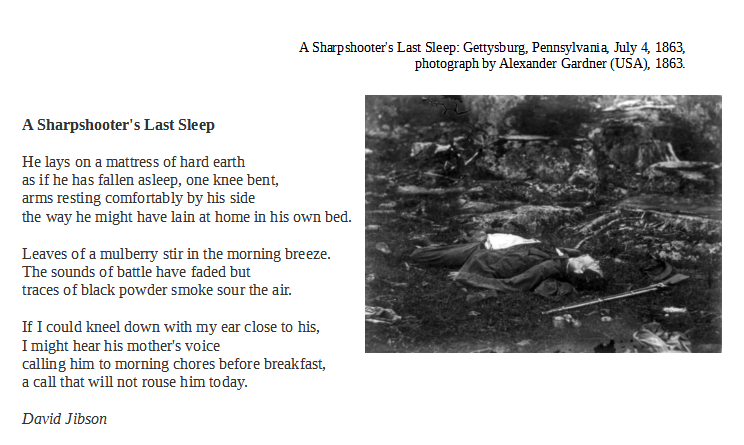

Writing ekphrastic poetry is a great way to break out of slump (I never say writer’s block). Here is a technique that makes an ekphastic poem seem to write itself. To demonstrate we’ll use a poem that was originally published in The Ekphrastic Review. It was insprired by the famous photo of the same title as the poem.

The poem is written in three parts, each part it’s own stanza, though that is not any kind of rule. It’s just how I chose to work with this short poem. I think it’s brevity contributes to it’s impact.

The first stanza is a simple description of what’s seen in the photograph. It’s best to concentrate on just one or two details and extend them, perhaps through comparison using simile or metaphor.

In step two I have brought in sensory experiences beyond the visual. This animates the photograph, turns it into a living scene that includes movement and the senses of hearing and smell.

The final step is for the poet to enter the photograph and to interact with the visual elements. This is purely imaginative and the most engaging part of writing the poem. You can talk to people, touch or pick up objects, use tools, taste food etc.

There you have it, short and sweet; 1) Describe, 2) Animate, 3) Enter and interact.